Past issues

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

ADRR Panel Discussions on Critical Issues, Problems & Opportunities

The Future of Downtown Multifunctionality

August 25, 2024

Partner Organization:Downtown Colorado Inc

Panelists:Michael Berne, MJB Consulting; Paul Levy, Center City District, Philadelphia; David Milder, DANTH, Inc; Terri Takata-Smith,Downtown Boulder Partnership

As we consider the future of downtowns, it is of growing importance to have a proper understanding of downtown functional districts. There is an increasing need for them to become more functionally diverse, but that will require an understanding of the array of economic functions upon which a downtown can be sucessfully based, where they should be located, how they should relate to each other, and how they should be packaged in the buildings that contain them. Join Downtown Colorado, Inc. (DCI) as we explore the future of multifunctionality in our downtowns in partnership with the American Downtown Revitalization Review (ADRR) to present a webinar panel with Micheal Berne, MJB Consulting, Paul Levy, Center City District, Philadelphia and David Milder, DANTH, Inc. moderated by Terri Takata-Smith, Downtown Boulder Partnership.

As we consider the future of downtowns, it is of growing importance to have a proper understanding of downtown functional districts. There is an increasing need for them to become more functionally diverse, but that will require an understanding of the array of economic functions upon which a downtown can be sucessfully based, where they should be located, how they should relate to each other, and how they should be packaged in the buildings that contain them. Join Downtown Colorado, Inc. (DCI) as we explore the future of multifunctionality in our downtowns in partnership with the American Downtown Revitalization Review (ADRR) to present a webinar panel with Micheal Berne, MJB Consulting, Paul Levy, Center City District, Philadelphia and David Milder, DANTH, Inc. moderated by Terri Takata-Smith, Downtown Boulder Partnership.

You can register for this free webinar by clicking this link REGISTER

Michael J. Berne, President, MJB Consulting

Michael is one of North America’s leading experts and futurists on urban and Downtown/Main Street districts as well as the retail industry more generally. As the Founder and President of the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City-based MJB Consulting, Michael has amassed more than twenty years of experience in conducting retail market analyses, devising tenanting strategies, and spearheading implementation efforts across the U.S., Canada, and the U.K., including a number of assignments on the Front Range. Michael is a regular presenter and keynote speaker at industry conferences, including those of the International Downtown Association (IDA), the National Main Street Center, the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC), the International Economic Development Council (IEDC), the American Planning Association (APA) and the Urban Land Institute (ULI), among others. He teaches courses for the IEDC and has lectured at both Penn and UC Berkeley. In addition to his widely followed “Retail Contrarian” blog, Michael has penned numerous articles for ULI’s Urban Land, written pieces for CNU’s Public Square and Dow Jones & Co.’s MarketWatch as well as authored a chapter for the book “Suburban Remix: Creating the Next Generation of Urban Places.” He has participated in several ULI panels and served two terms on IDA’s Board of Directors, including a stint as Vice Chair of its Executive Committee

Paul R. Levy, Chairman of the Board, Philadelphia’s Center City District

Paul was the founding chief executive of Philadelphia’s Center City District (CCD) and served in that capacity from January 1991 to December 2023. He now serves as the chair of the CCD board and the executive director of the Center City District Foundation, raising funds for CCD special projects and is continuing to manage two major capital projects of the District

The CCD is a business improvement district with a $31 million annual operating budget, which supplements municipal services with programs for security, hospitality, cleaning, place marketing and planning, business retention and attraction for the central business district of Philadelphia. The CCD has also financed and carried out $160 million in streetscape, lighting and façade improvements, including the transformation of four downtown parks that are now managed and programmed by the CCD (www.centercityphila.org).

He has consulted with a broad range of North American, European, Australian and Japanese cities on downtown and town center management

He serves on the board the Philadelphia Convention and Visitors Bureau. He also teaches in the graduate City Planning Department of the University of Pennsylvania and holds a Masters and Ph.D. from Columbia University.

N. David Milder, President, DANTH, Inc., and Founding Editor of The ADRR.

David has completed leading edge work on downtown central social districts and functions, arts districts, multichannel retailing, downtown fear reduction, as well as numerous retail assessments and downtown revitalization strategies for clients such as: Meredith, NH; Maplewood, NJ; West New York, NJ; the City of Gering, NE; the Village of Sherwood, WI; the Morristown Partnership (NJ); the Long Island City Partnership (NY); the Grand Central Partnership and4th Street Partnership in Manhattan; Jamaica Center, NY, and the City of Peoria, AZ. Since 1990, when many experts felt downtowns could no longer be successful retail locations, David has formulated numerous niche-based retail revitalization strategies that have stimulated growth in communities across the nation. He is the author of three books on crime and downtown economic development, downtown niche revitalization strategies, and downtown business recruitment, as well as numerous articles on Central Social Districts and functions, and increasing downtown functional diversity.

Terri Takata-Smith, VP of Marketing & Communications, Downtown Boulder Partnership

Terri is an experienced marketing and PR strategist with nearly two decades on the Downtown Boulder team. She specializes in developing and implementing comprehensive marketing/promotional campaigns and communication plans. Terri is a 2020 International Downtown Association (IDA) Emerging Leader Fellow and received IDA’s Leadership in Place Management (LPM) certification in 2022. She currently serves on the board of directors for Downtown Colorado, Inc. and Visit Boulder.

Article

Learning From Manhattan’s Third Major “Downtown”

July 11, 2024

N. David Milder, DANTH Inc.

Introduction[1]

I hopefully suspect that many readers will be prompted by the title of this article to ask: What downtown can he possibly be thinking about? Manhattan only has two major downtowns, Midtown and Downtown, possibly an evolving one in Midtown South, and a minor one in Harlem!

Such queries allow me to make one of my most important points in this article: we overlook or misidentify existing and important downtowns because of outdated and erroneous suppositions about what makes a downtown a downtown, being a very important highly urbanized place! That can happen in a multitude of ways, but some very significant ones are:

- A limited view of what its dominant uses/functions can be, usually with a focus on those associated with what conventional professional wisdom calls Central Business Districts (CBDs). CBDs have framed too many discussions and analyses of our downtowns as they emerge from the Covid crisis. With such an analytical perspective the presence of large clusters of office workers is usually the dominant downtown defining use/function, while other clustered uses such as residential, the arts and healthcare can go unnoticed as providing the socioeconomic spines for a strong downtown or strong urbanized place. Today, as questions arise about how important housing growth can be for our downtowns, being able to identify downtowns with very large amounts of housing could be very instructive. To date, I have not come across any putative examples mentioned by others of successful downtowns where housing is a truly dominant function, so I have been seeking them out. I think I found one, as described below.

- The primary, most important characteristic of a downtown, de facto, is seen as its real estate, not the people and organizations who use and give purpose and value to that land and the structures built on it.

- The requirement that the area in question has, in some important sense, geographic centrality, i.e., it is at the center of a region, city, market area or labor shed. Yet a good number of downtowns are not at the center of their cities (e.g., Uptown Charlotte, NC) or regions (e.g., New Brunswick, Elizabeth, et al in NJ), and many others (e.g., Englewood, NJ and Jamaica Center in Queens) are not at the center of their market areas. However, I do think that the urban agglomerations we call downtowns can have another kind of centrality, that of being a focal location for a high amount of activity in one or more intertwined uses/functions. It’s centrality is determined not by its location but by what is happening there. For this reason I have even argued that we stop using the term downtown and use City Central [2] Alas, that suggestion has not caught on.

- The related expectations of uniqueness and contiguity — all of the parts of the downtown in question are expected to be in one contiguous area, and not geographically very close to another downtown. However, in the 31 county NY-NJ-CT Metropolitan Region, one might reasonably argue that there are several downtowns other than those in Manhattan, e.g., Jersey City, Newark, Downtown Brooklyn, Long Island City, perhaps even Stamford, that are not that far from each other. There are many instances where even water separations are not that great, e.g., Downtown Jersey City is about 0.5 miles across the Hudson River from Downtown Manhattan with water taxis connecting them. On land, Midtown Manhattan is about 2.5 miles north of Downtown Manhattan. Importantly, Levy and Gilchrist have found that a significant number of cities are multimodal when it comes to employment nodes.[3] Since downtown boundaries are the result of some human(s) defining them, it is quite possible for these multiple nodes to be defined or redefined into two or more very proximate downtowns.

What Is a Downtown?

While I am not prepared to claim that I have a complete definitive answer to this question, I am confident that the following provides a solid foundation for arriving at one.

I have come to see the urban phenomena to which the term downtown is usually applied as a type of socioeconomic organism/system in which the primary players are the people and organizations that densely occupy and utilize built facilities in a specific land area. When properly functioning it is a very magnetic agglomeration of some sort and strongly activated with lots of visitors, and venues filled with patrons. It will feature one of a large number of possible combinations of uses/functions — a lot of different kinds of downtowns are theoretically possible. Its boundaries can be in a process of constant change as the number, types, and locations of uses grow, decay or relocate.

Downtowns differ from shopping centers, malls, office parks, and even some public spaces that also might share many of these characteristics because they are one or more of the following:

- Not owned and managed by one entity

- Far less likely to have clearly defined and long standing boundaries

- Far more likely to be seen as an integral part of the local community, winning the psychological attachment of a significant portion of the local population, and the source of local pride

- Less reliant on automobiles to bring users into the area in big cities

- Generally far more functionally diverse, save for the shopping malls that have intentionally aimed at emulating downtown multifunctionalism

- More organically developed, and less likely to be the product of one design plan.

Downtowns can accommodate a wide variety of uses/functions, and vary in the degree to which one of them dominates what the people who live, visit or work in it do. Working in offices need not always be the dominant, strongest use/function. Venues associated with their Central Social Functions that deal with how these visitors connect, live, and play can be of great importance, and in our post Covid-crisis world more and more downtown leaders are trying to make theirs much stronger.

The strength of these agglomerations we call a downtown can be measured in four basic ways:

- Their level of activation and magnetism, i.e., the number and types of people and organizations that live, play, work and do business there, how frequently they visit, and how long they stay. Basic, easily doable research in this area can lead to important insights. For example, recent impressive research by Paul Levy and his staff at the Philadelphia Center City District (CCD) on our 26 largest downtowns found that most downtown visitors do not come to work there.[4] This finding alone indicates that other functions/uses are very important parts of our downtowns and strong determinants of their strengths and success. Even simple stats on foot falls and venue attendance can be invaluable indictors of a downtown’s activation, probable levels of fear, and the attractiveness of street level business locations.

- The number and strength of its uses/functions that are capable of drawing substantial numbers of visitors and business transactions from areas beyond its five-minute walk shed. Uses/functions with such reach are more than just supportive of the dominant ones, and strong in their own rights.

- The level of attachment downtown users develop for specific downtown venues as well as for the downtown as a whole. Also, the level of attachment downtown organizations have for their locations, patrons, and the downtown as a whole. It is astonishing to me how very few urban theorists take user attachment into consideration. Jane Jacobs, if memory serves me, noted the importance of residents becoming attached to their neighborhoods, but few other analysts to my ken have followed suit, especially with reference to our downtowns. Strong attachments are likely to correlate with higher visitation rates, greater tolerance of temporary missteps, strong support for needed remedial actions, and strongly positive word-of-mouth communications.

- The economic impacts of downtown visitors and organizations in terms of jobs, career opportunities, social mobility, property values, tax revenues, etc. Research on these impacts are certainly warranted and important. The problem is that it has been the dominant way analysts view how our downtowns are doing. The recent widely publicized doom loop analysis of our downtowns is a perfect example of this.

Identifying the Upper East Side as a Downtown

My conclusion that the Upper East Side of Manhattan is a downtown is the result of my greatly increased visits to the area since about 2014 and my emerging view of what the agglomerations we call downtowns really are about that I have been slowly developing over the past decade, and outlined above.

In my four score plus years I have made loads of visits to the arts and cultural institutions in this area. They include several world class art museums and several others of substantial merit such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Frick Museum, the Neue Galerie, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, the Goethe-Institut, National Academy Museum and School, Museum of the City of New York, El Museo del Barrio, and the Museum for African Art. Most of them are in a one mile long cluster along Fifth Avenue. Also in the area are countless art galleries. Even the departure of the Whitney Museum to a southern Manhattan location has not substantially diminished the magnetism of this arts niche. They draw a large number of visitors to the area, many of whom are foreign tourists.

It also has what is perhaps the greatest public space in the US and perhaps even the world, the 836 acres of Central Park. I have been visiting this park since I was a toddler, joined these days by about 42 million other visitors each year. [5]

However, until recently it did not dawn on me that these arts venues and the park could be part of a downtown. A major reason for this is that Fifth and Park Avenues and so many other avenues in the area are so heavily residential, over 215,000 residents, and they are among the wealthiest and most powerful in the city.

The luxe retail along Madison had long perplexed me. It, like Rodeo Drive, was embedded in a large wealthy “neighborhood,” but it abutted the Midtown Downtown and was plainly drawing a lot of tourist shoppers. Was there some kind of connection with Midtown’s downtown? But it took me a while to ask if it was part of an Upper East Side Downtown.

Moreover, I too had associated a downtown, certainly one in Manhattan, with large office clusters, and I had not noticed any in the Upper East Side.

However, starting around 2014, I began to make a lot more visits to Manhattan. I soon noticed how widespread medical offices were along the eastern portion of the borough. Most of my visits were to those on the Upper East Side between 63rd St and 74th St east of Third Ave. Within that area are the home campuses of the Cornell part of the New York Presbyterian Hospital (NYP), the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), and the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS), as well as the Manhattan Eye and Ear Hospital. I also noticed just how much space these medical buildings occupied, and that they appeared to be spreading into adjoining areas down into the 50s and up across E72nd St. A significant number of these medical buildings were for research and teaching. Thinking about it, it seemed that while a lot of this healthcare space was referred to as offices, a lot of what happens within them is not very comparable to what happens in traditional office spaces. One must make the distinction between the type of physical space—that is, it looks like an office—and the uses therein. Health treatment is a personal service, research is part of the R&D sector, and teaching is education. Many communities target “Eds and Meds” as a business cluster they have or want as a key part of their economy.

More recently, as the impacts of remote work sparked suggestions about downtowns substantially increasing their residential populations, it struck me that this area also has a very substantial amount of high rise residential buildings, and a large amount of neighborhood retail, some comparison retail, and personal service operations to serve local residents and those who work in or visit the area’s healthcare operations.

As my thinking about what a downtown has progressed, I began to see this area as activated, economically important, and a possible downtown or unnoticed node of the Midtown agglomeration. It is a heavily used area, with a lots of jobs and residents, and many visitors to doctors’ offices and patients in its hospitals. It differs from its Midtown and Downtown brethren in having healthcare and residential uses being the most important ones instead of traditional office space uses such as finance,; real estate, insurance, information, and professional, scientific and technical services. The healthcare operations were making this area something a lot more than a neighborhood for wealthy people, while the large residential population was making it a lot different than one dominated by a huge healthcare cluster, as the sterile Cleveland Clinic campus has done to its neighborhood. I began to ask myself if this was a downtown and found it hard to deny that possibility, though it probably would be seen as an unusual one because of its untraditional mix of dominant functions.

The really important point here is not whether this agglomeration is a downtown or a node of Midtown, but that it is a largely unnoticed, strong socioeconomic agglomeration with a set of dominant uses and functions — healthcare and housing — that are quite different from those (office work) conventional wisdom, as often expressed in the media, associates as defining downtown characteristics.

Since my focus on healthcare was driving my analysis, my next challenge was how to deal with two other large hospitals on the Upper East Side: Lenox Hill Hospital that occupies almost a complete block between 76th and 77th Streets and between Lexington and Park Avenues, and Mt. Sinai Hospital that runs along Madison Avenue from 98th to 101st Streets and has a strong Fifth Avenue presence. As a consequence, I engaged in a little mind experiment that expanded my geographic definition of the Upper East Side Downtown to 101st and 60th Streets on the north and south, Central Park on the west and the East River to the east and then looked at what uses/functions that expanded area now also contained:

- The two hospitals

- All the high priced luxury apartments along Fifth and Park Avenues

- The large number of doctors’ offices occupying ground floor spaces in these buildings, especially along Park Ave where almost every residential building has such spaces

- The large number of arts related venues I described above, many of them of world class stature

- The long and strongly rebounding luxe retail corridor along Madison Ave

- Most of the eastern border of Central Park.

The Upper East Side certainly has a large number of wealthy people living in it, but my observations as detailed above unquestionably support the conclusion that it is a whole lot more than just a large, wealthy residential neighborhood. It is very functionally diverse, with healthcare, the arts and retail being very strong uses that serve local residents, but also draw large numbers of visitors and workers from well beyond the neighborhood. Tourists, for example, account for a very high proportion of its museum visitors. Its museums and Central Park attract millions of visitors annually. The hospitals also draw a significant number of patients and visitors, though probably not as much as the arts. Matthew Bauer, President of the Madison Avenue BID, reports that merchants believe about 40% of the Avenue’s shoppers are visitors. Many of them visit regularly and have sales associates at the Avenue’s shops they look for and deal with, indicating just how strong this visitation is.[6]

While the Upper East Side may lack large traditional office clusters, it still is the location for a significant number of jobs. In zip code 10065, for example, home of the Cornell part of NYP and MSK, in 2021 there were more jobs, 44,000, than residents, about 31,000.

This article is the conclusion of my little mind experiment. I cannot see any supportable reason for not calling Manhattan’s Upper East Side a downtown. It is a large, well activated agglomeration and, importantly, quite different from most of our other large downtowns:

- Housing is its strongest use/function

- Healthcare, the arts, and retail are three other very strong uses/functions

- Traditional offices are present but are not a major use or function

- It borders another large strong downtown that has a quite different array of uses/functions.

Recognition of Its existence demonstrates that very powerful urban agglomerations can exist that are not Central Business Districts. It also supports the argument that these places we call downtowns can survive and prosper even with diminished office clusters, and that housing can be the strongest function in such successful agglomerations.

Pushbacks to suggestions that downtowns should substantially increase their residential populations have sometimes involved requests for examples of downtowns where the residential use is dominant, or explanations of how a downtown can survive without large office clusters. Recognition of the Upper East Side agglomeration as a downtown more than amply satisfies those requests.

ENDNOTES

[1] I want to acknowledge and thank Mark Waterhouse for the great editing he did on an earlier version of this article.

[2] N. David Milder. “A Search for a Clearer and More Useful Vocabulary for Talking About and Analyzing Downtowns.” Downtown Curmudgeon Blog, December 14, 2021. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2021/12/a-search-for-a-clearer-and-more-useful-vocabulary-for-talking-about-and-analyzing-downtowns

[3] Paul R. Levy and Lauren M. Gilchrist, “Downtown Rebirth: Documenting the Live-Work Dynamic in 21st Century U.S. Cities.” Prepared for the International Downtown Association by the Philadelphia Center City District, 2013, pp.57

[4] Paul R. Levy, ‘Downtowns Rebound: The Data Driven Path to Recovery’, Center City District, (October 2023) available at https://centercityphila.org/downtownsreport.

[5] To maintain analytical rigor it should be noted that the 42 million visitors coverts into an average of only about 136 visitors per acre per day.

[6] In an email from Matt Bauer on July 2, 2024.

Article

RETHINKING THE THINKING ABOUT DOWNTOWN CULTURE/ARTS/ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICTS … and for that matter, all kinds of downtown monofunctional districts

June 11, 2024

N. David Milder, DANTH, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade my work on Central Social Districts (CSDs), downtown arts districts, and 15 minute communities has led me to time and again see the weaknesses in using districts as the key geographic unit of analysis. For instance, I concluded that because the CBDs and CSDs refer to overlapping or the same areas in a downtown, it is better to just use the terms downtown, Central Business Functions, and Central Social Functions.[1] Of course, despite that effort, the use of the term, especially its CBD variant, persists and the downtown itself and some of its subareas such as its theater or major office clusters are all referred to as districts. Consequently, though work-arounds are possible, analysts seldom give the district concept the analytic attention it requires since they seem to wrongly assume the concept’s meaning, and proper applications and definitions are well known and humdrum.

However, as a result of the serious problems many downtown office clusters are facing, the value or tolerance of monofunctional districts has lost considerable favor, and many downtowns are rushing to increase their functional diversity. At the same time, with the increasing recovery of our downtown culture/arts/entertainment (CAE) venues and the increased drive for more functional diversity, one might anticipate that growing CAE assets will be a frequent goal, and using CAE designated downtown districts will be a frequent tool for achieving it. Consequently, it is of growing importance to have a proper understanding of downtown functional districts.

That said, I want to be clear that I am not calling into question the use of the term district when applied to municipally designated downtown assessment areas, i.e., business improvement districts.

A reviewer of an earlier draft of this article noted that I provocatively raised more issues than I resolved. That pleased me since I hope this article provokes others to think seriously about downtowns, their clusters and districts, and the need to achieve functional diversity.

DOWNTOWN MULTIFUNCTIONALITY WAS OFTEN THE RESULT OF A LOT OF SUB-DOWNTOWN MONOFUNCTIONALITY.

The very names of many of our downtown districts indicates what makes them so problematical: e.g. the central business district, the theater district, stamp district, furniture district, antiques district, flower district, diamond/jewelry district, the garment district, the arts district, the financial district, Chinatown, etc. All of these names denote the presence of one very dominant use/function, and while these districts probably have some other uses present, they only play supportive roles by serving those who work and visit the venues associated with the district’s dominant use. A tell of these supportive functions in our large downtowns is that they seldom draw meaningful customer traffic from areas beyond about a five-minute walk from their locations.

There is a very good reason that the district concept has had such a long and largely unquestioned standing and use among those who analyze and mange our downtowns: for many decades our downtowns were an aggregation of several of these monofunctional districts. For example, there were reportedly well over a hundred of them in Manhattan decades ago. Office buildings were far from the only use that developed into monofunctional clusters. The multifunctionality that observers often noted as a defining characteristic of our downtowns was regularly mainly the result of a lot of monofunctionality at the subdowntown level! It is important to note that the monofunctional downtown districts of yore are generally more properly referred to as unorganized clusters of venues, each associated with a particular use/function.

DESIGNATED ARTS DISTRICTS

Most of these downtown monofunctional districts were the product of organic growth resulting from a downtown neighborhood having congenial locational assets for a particular use/function. Others were the result of the planned construction of several buildings focused on meeting the needs of a particular group of users, such as the World Trade Center focusing on office uses and Lincoln Center being built as a major Performing Arts Center. Others were the result of a municipality “designating” an area in the downtown or elsewhere in the city as a special place for a particular use/function for non-health or safety reasons, but to support and incentivize the marketing and growth of that particular use/function. Such designations may provide favorable zoning, but the incentives offered often go beyond that if they are properly designed and organized.

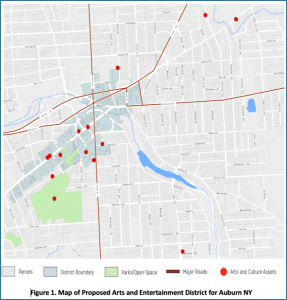

While many of these downtown monofunctional districts have disappeared, for reasons that will be discussed below, pre-Covid19 there was a significant movement to create new CAE districts in communities across the nation that were meant to support the marketing efforts and growth of CAE venues in particular areas in or near a downtown. Such “designations” often are geographically defined to include important existing CAE venues (see Figure 1) and meant to make them stronger, while attracting new ones. However, such geographic designations are often problematical. Many arts districts fail to include all or even most of a city’s arts venues. Also, the prior organic development of these CAE venues is often quite dispersed (see Figure 1), challenging any connotation of their interacting with each other that the term district might have. More about that below.

While many of these downtown monofunctional districts have disappeared, for reasons that will be discussed below, pre-Covid19 there was a significant movement to create new CAE districts in communities across the nation that were meant to support the marketing efforts and growth of CAE venues in particular areas in or near a downtown. Such “designations” often are geographically defined to include important existing CAE venues (see Figure 1) and meant to make them stronger, while attracting new ones. However, such geographic designations are often problematical. Many arts districts fail to include all or even most of a city’s arts venues. Also, the prior organic development of these CAE venues is often quite dispersed (see Figure 1), challenging any connotation of their interacting with each other that the term district might have. More about that below.

These efforts to create designated CAE districts tended to be led by those who believed that the arts can be a very powerful engine for economic growth, and was backed by such organizations as Americans for the Arts that advocated for creating culture districts. Some impressive headway was made in a few states, such as the development of 30 “Creative Districts” in Colorado between 2011 and 2024. On the other hand, a master plan for the creation of downtown arts districts in five Central NY cities — Auburn, Cortland, Oneida, Oswego, and Syracuse — published in 2019 has not moved forward. The Covid19 Crisis obviously probably had something to do with that, but how much is uncertain. That crisis probably also influenced Americans for the Arts to stop researching and marketing its culture districts concept, though it seems open to doing so should ample interest and demand return.

AS DOWNTOWN CAE VENUES RECOVER WILL THE MOVEMENT TO DESIGNATE MORE CAE DISTRICTS ALSO REBOUND?

Strong evidence suggests that the recovery of CAE venues in or near our downtowns has been surprisingly robust, if not yet complete. For example, as I have noted in another article, major museums and the Broadway theaters in Manhattan have recovered about 80% of their pre-crisis audiences, a figure that is bound to rise as foreign and business tourist visitors return in the near future.[2]

CAE venues in several other large downtowns have reported similar or even stronger audience recoveries. For example, the recovery of CAE venues in Downtown Los Angeles has been strong and its management is now planning to create a formal Grand Avenue Culture District–and for reasons that suggest that as our downtown arts organizations rebound, creating more downtown CAE districts will again attract supporters. This is how Nick Griffin, the Executive Director of the DTLA Alliance has summed up the current strategic importance of his downtown’s CAE functions: “The fact that the expansions of The Broad and The Colburn School are both based on demonstrable demand – growing student body and 500+ annual performances at Colburn and The Broad blowing their attendance projections out of the water by almost 4x within the first few years – speaks to the strength and appeal of Grand Avenue’s cultural institutions, and while they certainly took a hit during the pandemic, they are not only recovering well, they are positioned to play a key role in the reimagination of DTLA in the context of shifts in the office sector and growth in residential and hospitality…. I’ll note that our long-envisioned dream of creating a formal Grand Avenue Cultural District is finally taking shape, with funding in place and a kick-off planning meeting scheduled for next week!”[3]

TO READ MORE CLICK HERE

[1] N. David Milder. “A Search for a Clearer and More Useful Vocabulary for Talking About and Analyzing Downtowns.” Downtown Curmudgeon Blog, December 14, 2021 https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2021/12/a-search-for-a-clearer-and-more-useful-vocabulary-for-talking-about-and-analyzing-downtowns.

[2] N. David Milder. “Let’s Recognize And Leverage The Opportunities The Covid Crisis Has Given Our Downtowns.” Economic Development Journal, 2022, p34 https://www.dropbox.com/s/v9v5y0ovtxzlkco/Milder%20leverage%20crisis%20produced%20opportunities%20EDJ_Fall2022_final.pdf?e=1&dl=0.

[3] In an email communication.

Article

Downtown Retail, Mono-functionality, and Critical Mass

June 11, 2024

Michael J. Berne, MJB Consulting

In response to David’s article, I have a few thoughts to share.

I have grappled with this idea of mono-functionality with respect to certain types of retail — specifically, the concept of critical mass. Obviously, the importance of critical mass (and its close relative, co-tenancy) varies depending on the category, though arguably it is most critical with regard to comparison goods (e.g. fashion, home furnishings, antiques, etc.), where we as consumers have traditionally gravitated to larger destinations that allow for the greatest possible choice (i.e. for “comparison shopping”). The bigger the destination, the larger the addressable market — hence, the ever bigger “fortress” malls like Roosevelt Field, Garden State Plaza and King of Prussia as well as the massive clusters that we find on (an ever dwindling number of) urban high streets. Flight to quality indeed.

And yet, even some real estate professionals do not seem to fully appreciate the concept. Perhaps it is just willful self-interest, but a modest subset of landlords and brokers will routinely press for less restrictive zoning in comparison-shopping destinations so that they can more quickly backfill vacated spaces with non-synergistic uses like dental clinics and title companies — further reducing the number of options available to comparison shoppers which, once it falls below a certain threshold, can collapse in a hurry (as we see in the case of malls that lose major anchors).

Municipal planners are typically not attuned to such dynamics, either — hence, the initial recommendation in Mayor Adams’ City of Yes: Economic Development proposal to open the floodgates to non-retail uses on Madison Ave between 57th and 70th (!). For this reason, I often impress upon my public-sector clients the need, at least in certain cases, to be very careful, even (especially) during times of distress and hand-wringing, and to avoid panicking, as many unfortunately have done amidst the supposed “retail apocalypse” and then the pandemic. After all, once you allow in those (creditworthy) dental clinics and title companies, they ain’t going anywhere….

That said, my thinking has recently started to crystallize around a relatively new and different sort of destination, which I call, for lack of a better term, “browse-worthy.” It has shops — usually a mix of boutiques, chain-lets and maybe a few faux-boutique brands — but not anywhere close to a critical mass of them. And those shops are combined with compelling food and beverage — which is, as we know, what generates the buzz (and effectively serves as the anchor) in retailing these days — then packaged along with walkability, placemaking, maybe even a green space. People are not visiting these destinations expressly to shop but rather, to consume a place in its entirely — which calls for more functional diversity in the retail mix, rather than any sort of critical mass. They are also not going there out of convenience — many of them are nestled along intimate neighborhood shopping streets, far from a freeway exit or transit transfer. After all, with social media and third-party rideshare, inferior visibility and access are not necessarily dealbreakers.

I think, though, that there’s quite a bit more nuance to functional diversity than meets the eye, at least as it relates to retail. For one thing, not all non-retail uses are equal. Owners of B/C malls, likely out of desperation, will often employ a kitchen-sink approach to backfilling vacant retail space and land, but the result can be a jumbled mess that does not synergize at all — which might work for the pro forma, but not as any sort of cohesive destination that can pull from afar. Even the addition of a 100-unit apartment complex where a department store used to be — what does that really do, add 200 more customers to an increasingly irrelevant retail core? That’s not going to save the day, not in the long term….

Article

Some Comments On The Idea Of Thinking About, Analyzing And Planning For Cities At The District Level

June 11, 2024

Paul R. Levy,

In response to David’s article, I want to offer some comments on the idea of thinking about, analyzing and planning for cities at the district level, rather than simply talking about a large area called “the downtown.” Living in Philadelphia that had, when I arrived in 1976, an urban renewal demolition created office district and an Independence mall historic district created by clearing out an obsolete warehouse district, an urban renewal, preservation-created historic Society Hill residential district, an organic Fabric Row, Jewelers Row, Chinatown, Antique Row and a South Street alternative culture street that rebounded once plans were defeated for demolition and clearance of the entire corridor. I have watched these places evolve and change over time.

Having done the first master plan for our Avenue of the Arts district in 1990, while puzzling over how to handle the theaters to the east on Walnut street, that claim to be the oldest in North America, I very much appreciate your use of the term “archipelago” – recognizing that even defined districts, have geographic outliers. Clearly, the designation of South Broad Street as the Avenue of the Arts helps for marketing purposes; it helped leverage funding for streetscape and façade lighting improvements to reinforce the district, and it helped fundraising by new theaters that attracted donors and a governor who saw their investments not only in buildings but in the creation of a supportive district. We obviously agree on multi-functionality being a key to the future of arts and of all districts, but don’t leave out parking as unpleasant, but necessary support function for many theaters who rely on suburban customers. So from my experience, “districts” can be both organic or result from conscious planning by a city or by a developer who secures control of multiple sites.

Can or should districts be preserved? Sometimes market conditions change and, for example, the demand for certain types of property goes away and there is nothing that can be done to reverse trends if there is no an alternative viable use for those properties. On the other hand, Chinatown in San Francisco, emerged organically, like many other counterparts, but it was protected from pressures from the adjacent financial district by government imposing height limits and historic designation.

We are at one of those moments in the life of our cities where we need fundamentality to rethink what they are. In many similar prior moments, we have made huge mistakes and also done many things well. We have been captivated by the new-new-thing that turned out to have a limited life and we have tried to preserve things that had lost their reason for being. Somewhere in between is the right path to follow.

Article

A SUCCCESS STORY IN DALLAS

January 1, 2024

By Andrew M. Manshel, author of Learning From Bryant Park

Editor’s Note. An earlier version of this article appeared in Andy’s The Place Master blog.

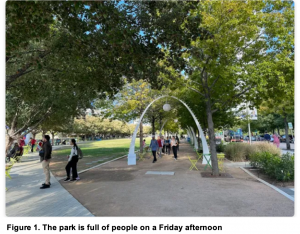

Clyde Warren Park in Dallas works. A recent visit, more than ten years after its opening, showed it to be heavily used and reasonably well managed. On a weekday afternoon the park had quite a few visitors, including lots of children.

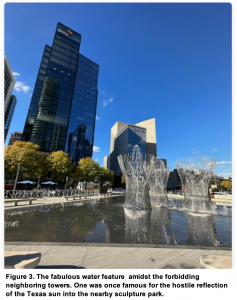

The park has most of the elements that make public spaces successful:

- Shade – essential in the southwest

- The one here is very cleverly designed and attractive – including fun water features

- Lawns

- Food kiosks and restaurants

- Water features

- Regular programming

- Movable chairs

- Adequate maintenance

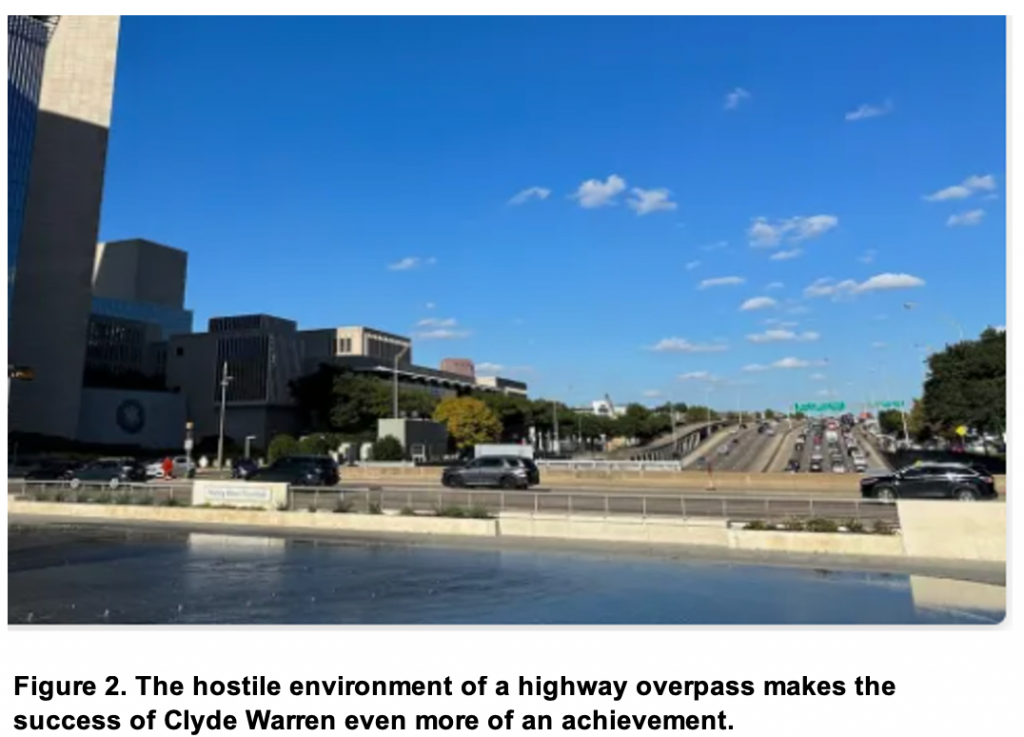

As we have written ad nauseum, there are so many new public space projects, and so few of them are successful. Clyde Warren was built over a highway culvert – a category of assignment that has proved particularly challenging for public space planners over the last couple of decades. Building over a highway cut can be an essential move in re-knitting a downtown together. But doing it right is a tough assignment. The designers of Clyde Warren, The Office of James Burnett, got what animates a public space on a deep level that seems to elude almost all landscape architects and public officials. After ten years, Clyde Warren is still performing well – attracting a broad swath of users. On the day we visited a large portion of the park was closed for a private event – but there was still quite a bit of space available to the casual visitor.

A good contrast with Clyde Warren is another public space in the southwest, Santa Fe’s Railyard Park of about the same vintage – which remains virtually unused, despite quite a bit of interesting development around it. The arts district of downtown Dallas is not the most promising or hospitable of environments for a public space. Downtown Fort Worth is way more walkable, human scaled and attractive. The surrounding streetscape to Clyde Warren is towers and institutions set back from the street – essentially bleak, unwalkable and car oriented. Prominent among the high design structures of the arts district (Rem Koolhaas, Norman Foster) are a large number of parking structures. But somehow, pedestrians find their way to the two large blocks that constitute Clyde Warren — most likely from the offices and residential towers that overlook the park.

The nonprofit that operates the park, The Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation, has an operating budget of around $15 million. The biggest challenge for public spaces with water features is keeping them running. And the features at Clyde Warren are complicated and fun to watch. The Foundation seems to have the resources to keep things running. The water features are open for kids (and adults) to splash around in – which is just great, and unfortunately not standard practice. These water features are complex and they work. Kudos to the park’s managers.

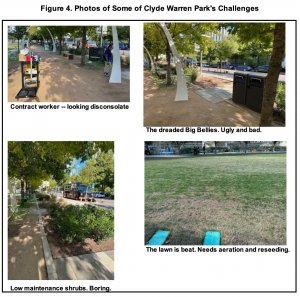

That not-withstanding, the Foundation appears to contract out for the park’s maintenance, and it shows. Outsourced maintenance is never as detailed oriented and perfectionist or as highly motivated, well-compensated internally managed staff. The park demonstrates a lot of wear from high use and is not kept to the high standards of Bryant Park. The lawn panels need aeration and reseeding. The horticultural elements are designed for low maintenance and aren’t well maintained even given that. They don’t have the kind of visual pop that a public space of this caliber really ought to have. Some of the arts institution facilities in the district have much more imaginative and appealing plantings nearby

Big Belly trash receptacles are in use – which are a bête noire of mine. They are a mark of managerial laziness. The design is awful – they are a squat box. The labor they supposedly save, is labor that the park really needs. Staff dumping out the trash bins are a visible mark of social order. Visitors want to see people working in the park – maintaining the horticultural elements and emptying the trash bins. It contributes to the perception of public safety.

But, as can be seen in Figure 5, those issues aside, Clyde Warren Park, is a clear model for others to follow as to what makes a park lively and attractive. The built environment in downtown Dallas makes creating lively public spaces a challenging task, and so the park’s success is even more a particular achievement.

A pdf version of this article can be downloaded HERE